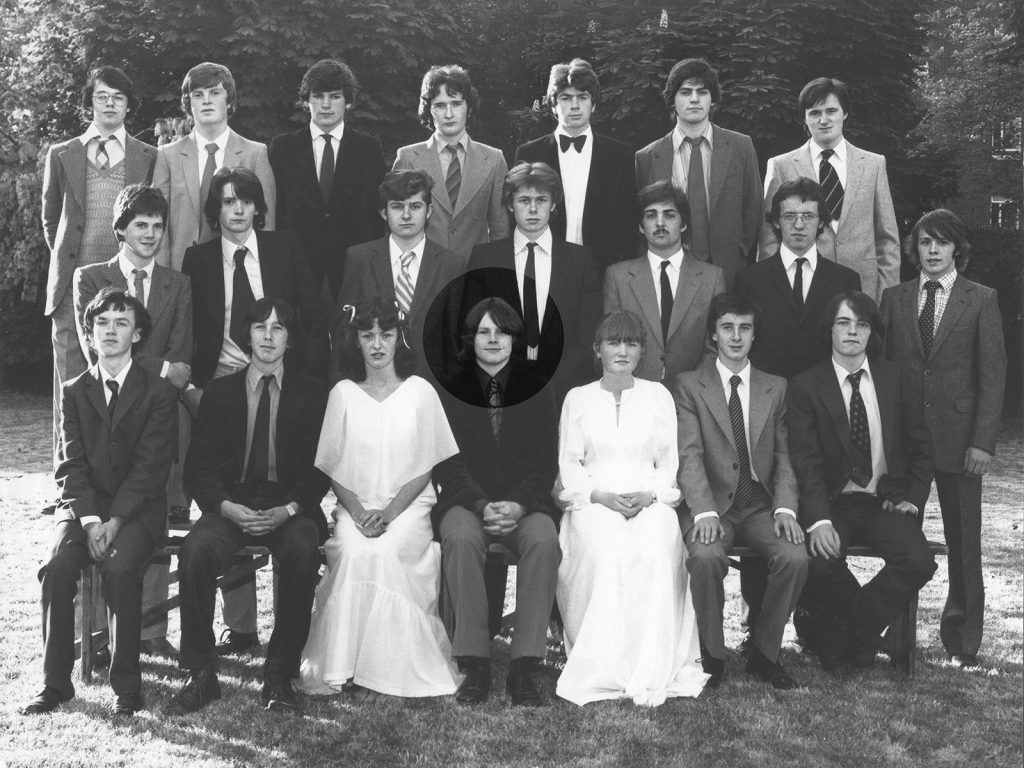

David Kelly

8 April 2021What I Learnt at School

I was born in Dublin, the son of a politician, and grew up about a mile and a half from St. Conleth’s. When I was six, my parents took me to be interviewed by Mr. Kelleher. This was always the expected path – my father and his brothers had gone to Conleth’s in the 1940s and my brother Nick, who is 15 months older than me, had entered the school a year before.

Either because he dazzled “The Boss” (as Mr. Kelleher was known) at his interview or because my father wanted to push him, Nick was put in third form rather than second, making him the second youngest in his class. I suffered a similar fate and my parents enrolled me in a class in which I was the youngest by six months. Strange as it seems, this one decision has probably had a greater impact on my life than almost any subsequent choice.

My first year at Conleth’s was traumatic. While I was able to follow along in class no problem, my handwriting was atrocious and I had no memory for spelling at all. Reports of my struggles reached home and Mr. Kelleher and my parents recognized that they had made a mistake and demoted me to second form.

This was a matter of deep shame for me, and as I had made friends in third form, I pleaded with the authorities to reinstate me and worked hard to convince them. They relented and let me back up. I slacked off and was demoted again. And then, finally, having shown some signs of promise in maths, they relented again and I returned to third form, doomed forever to be the youngest in the class.

After third form, I settled in. While I liked history, maths was the subject in which I got the best marks. Mr. Poole was an early maths teacher and a lovely man. I remember him helping me in my struggles to stay in third form and his belief in my ability. Over the years, I have become convinced that nothing is more important to success than having people who believe in you.

English was my worst subject. Truth be told, I wasn’t really bad at English – it was just that my handwriting was abysmal and my spelling entirely random. These faults, of course, have ceased to be impediments in the days of word processors. But they were serious issues to Mr O’Byrne, who would storm into the class, red in the face and foaming at the mouth, and slam our notebooks onto the desk in front of him. I didn’t really think of him as a gifted teacher. But the fear of incurring his wrath encouraged all of us to put a little extra effort into our compositions.

Fear was an important tool in maintaining discipline in Conleth’s. Mr. Kelleher and Mr. Murphy would patrol the halls in search of any boy who had been so wicked as to be sent out of the class. When they encountered such a criminal, they would lead him back into the class, inquire as to the nature of his crime and dispense summary justice. This came in the form of “six of the best” from the “Little Biffer”, a leather strap wielded by Mr. Kelleher, or the “Big Biffer”, a similar implement carried by Mr. Murphy. Mr. Murphy, although a very kind-hearted man, really didn’t know his own strength and I think classes were better behaved on days when Mr. Murphy was on duty in the halls.

In the evenings, I’d return home exhausted from school or rugby and had no energy for homework. So in the mornings, I’d get up early, cycle to school and frantically try to get my homework done before the bell rang. Often, I’d just complete the first class’s homework before it started and would sit at the back of the room, pretending to take notes while feverishly working on the assignment for the next class. I’ve been much the same with work ever since – there is nothing like a deadline to concentrate the mind.

I would also argue with our French teacher, Mr. Feutren. Mr. Feutren spoke quietly but truly scared us all, partly because of the rumours we’d heard about him siding with the Nazis as a Breton Nationalist in World War II. He could always be drawn into a political dispute and regarded me as a member of the decadent bourgeoisie. As a consequence, my classmates would egg me into getting into an argument with him to leave him with too little time to quiz us on our homework. I learnt more about debating than French from Mr. Feutren.

However, throughout my days at Conleth’s, my youth was always an overshadowing handicap. I was young, I looked younger and was naturally shy. While I had friends at school, I felt pretty isolated as a teenager and probably didn’t build the social connections that I could have done had I been in a class closer to my age. This continued in university, which I entered at age 16, and probably had some influence on my decision to go to graduate school in America.

When I entered sixth year, I applied to do Arts in U.C.D.. I think Mr. Kelleher was disappointed as he thought, with my maths skills, that I should be going for a more prestigious place in engineering or medicine. But I wanted to study economics with an idea that it would be useful if I went into politics. Undergraduate economics left me with more questions than answers and I decided to do a Ph.D. I was also attracted by the adventure of attending graduate school in the States.

So, in 1983, I went to Michigan State University where I was lucky enough to acquire a Ph.D. and meet my wife, Sari, who has now had to put up with me for over 35 years. I wrote a dissertation in applied econometrics and we moved to Boston in 1990, where we have lived ever since. In 1994, I joined the now infamous Lehman Brothers and acquired a CFA designation.

In 1999, after a brief sojourn with a Swedish asset manager, I applied for a job as an economic advisor to Putnam Investments. This involved plenty of writing but also media appearances and delivering speeches across the United States. Finally, in 2008, as the Great Financial Crisis was unfolding, I moved to JPMorgan. I now work as the Chief Global Strategist for JPMorgan Asset Management and have the good fortune to run a team of 25 young, energetic and talented strategists and analysts around the world.

I was asked, when compiling this account, to mention any achievement of which I am particularly proud or any advice I might have for someone wanting to pursue a career in finance.

As to achievements, I have nothing extraordinary to my name. However, I do think, over the years, I have helped people understand the nature of the economy better and, by calming both their wildest fears and most exuberant hopes, helped them make better investment decisions. I also feel good about the number of people I’ve supervised over the years who I honestly think I’ve helped in building their careers.

On advice, first be a good person. In business, surprisingly, it has been my experience that good people finish first because people want to work with them. Second, learn how to communicate. Finance is full of numbers people who cannot write vividly or speak convincingly. So read the work of great authors to make yourself a great writer. Also, speak up at meetings and make your voice heard. It is much better to say the occasional stupid thing than to never speak at all. Finally, knock on doors, even if it feels uncomfortable. You really never know where the next opportunity will come from but you are much more likely to find it if you are brave enough to go looking.